Armenian News Network / Groong

August 10, 2009

By Arthur Hagopian

JERUSALEM

It was a soothingly welcome relief from the shivering cold that had gripped Sydney as I boarded my flight, barely a day earlier.

|

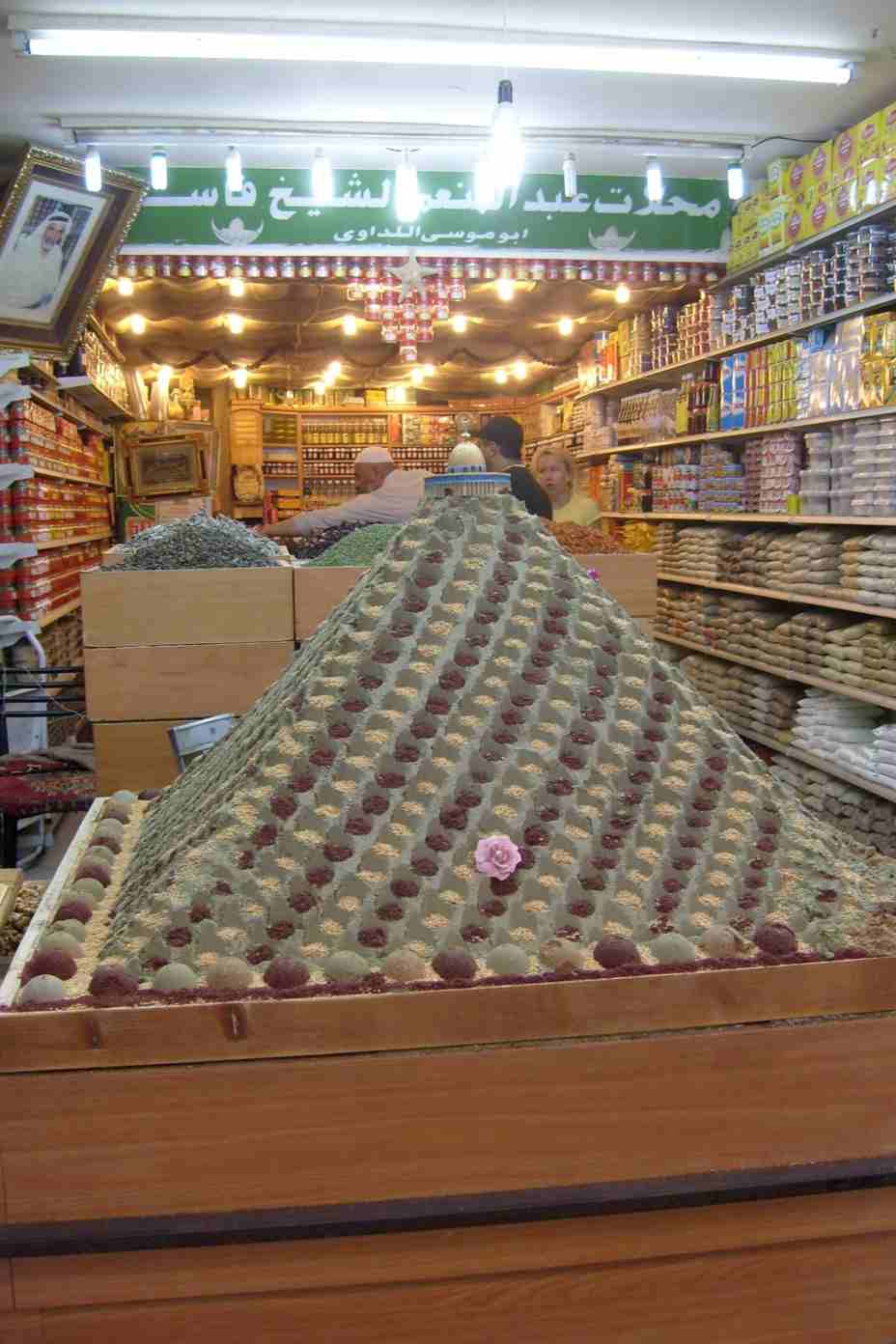

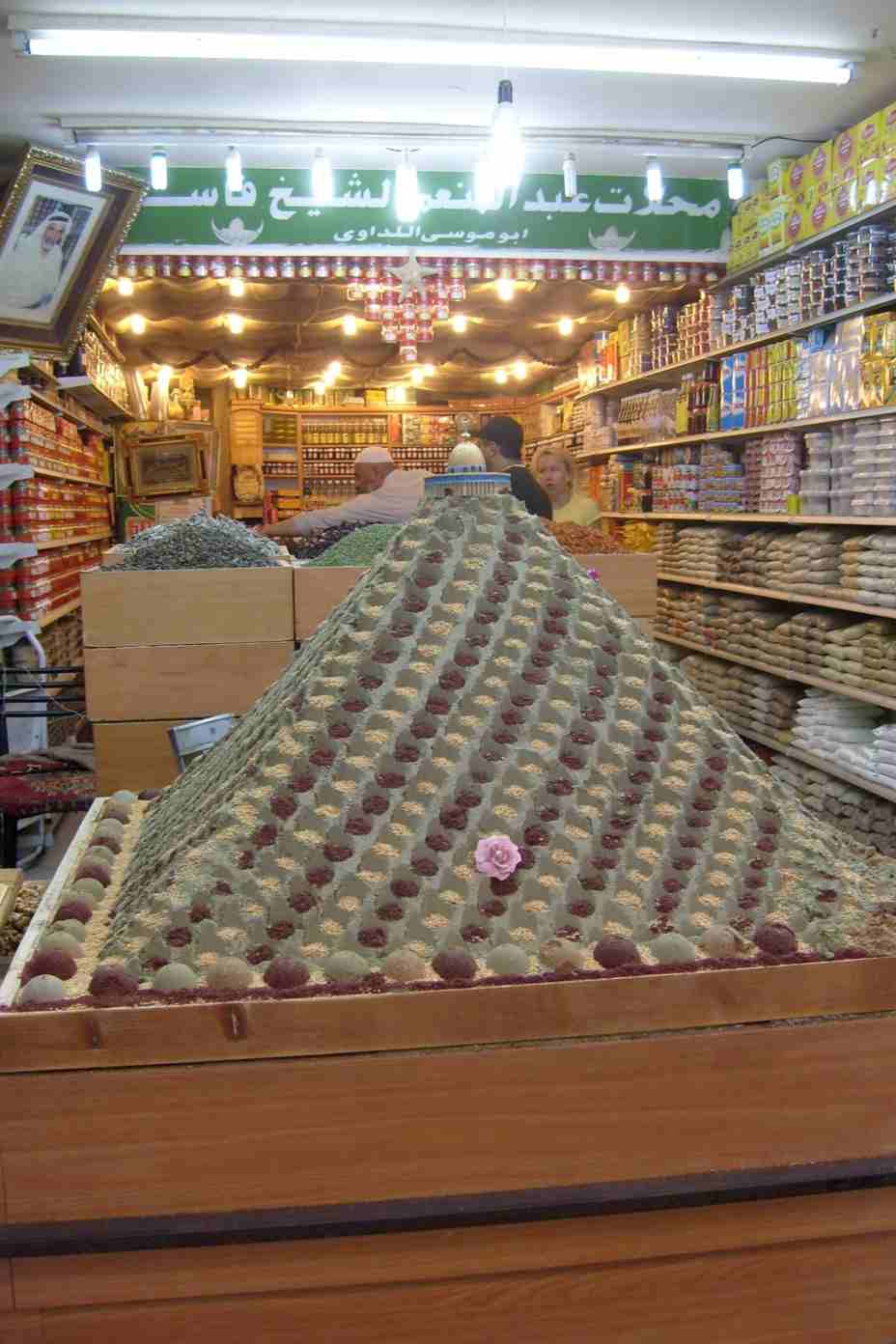

| Old City spice merchant |

Cars and people moved in equal abandon along the ribbon of the only road open to traffic inside the Old City, the cries of the Arab vendors adding their strident yet mellifluous note to the cacophony of horns and assorted noises.

Nothing seemed to have changed in the 15 years I had been away. The Christian Quarter still maintained its metamorphosis as a sprawling tourist bazaar. Abu Shukri and Ja'afar, two of the most popular eateries in the Old City, had jumped on the expansion bandwagon and branched out, the first into a nearby location, the second beyond the boundaries of the metropolis.

The Christian Information Office, operated by the Franciscan fathers, traded jaded glances with the Citadel opposite but further down the road, the Kalaydjian family that had inherited what was probably the Old City's most famous grinding mill, had finally decided to dismantle that anachronism and put their shoulders to the task of transforming the site into another watering hole.

The venture has turned out to be a pleasant success. And they have kept the nickname, Bulghourji, by which everyone knew their former enterprise.

As I tread along the old familiar paths, I am overcome by the overwhelming sense of the time continuum and the ethereal touch of imperturbability that Jerusalem can inspire.

Along these roads had walked a progression of prophets and teachers of righteousness. The feet of countless conquerors had pounded these stones in their quest for immortality. Jerusalem, city of gold. City of mystery. It is not possible to talk of Jerusalem except in superlatives. But no matter how you describe one of the most sacred spots on earth, it is clear that there can never be any consensus on Jerusalem.

There never was. There never will be. You either love it or, if you have no poetry in your heart, you shrug it off.

For some, it is the vision of sanctity and purity that appeals to them. And when they come here, they carry with them expectations of a spiritual rebirth in a new baptism of revived faith as they quaff from the waters of Jerusalem. There is no mistaking the look of almost childlike anticipation lighting up the features of pilgrims who had braved the travails of long travel in their odyssey.

In the euphoric aura in which they envelop themselves, they remain unfazed by what looks like an armed camp, with security forces around almost every corner and guns bristling everywhere.

Most of the police and soldiers are young, some in their teens.

I look at the people around me - so many of them wizened clones of younger selves I had known years before, most of the others strangers.

My progress along the street is punctuated by the milestones of a contingent of friends from my youthful years in Jerusalem. We greet each other with hugs and kisses and plenty of backslapping. (Middle East tradition stipulates that the kisses should be three in number, and placed upon the cheek, and not into empty air).

There is Hoppig Marashlian, leaning against a parapet, waiting for her niece. She is eternally cheerful, with a repertoire of jokes and anecdotes to lighten anyone's day. She greets me with a boisterous buss and brings me uptodate on what is going on in the Armenian Quarter where she lives with her widowed mother and brother.

"Shbeeni," she calls me as she unabashedly sizes me up. I am her godfather, her "shbeen." It is an old Armenian church tradition that when a child is to be christened, it must be swaddled in white and carried in the arms of a male relative during the ceremony. I had been invested with that duty. Some consider it a privilege.

A hundred feet away, the ramparts of the Old City meander down into the valley of Siloam. I am enraptured by their captivating contours, and dawdle blissfully along the way. Zion Gate, which still bears the wounds of war inflicted upon it during the 1948 Arab-Israeli war, is just around the corner.

I climb the bastion atop the gate. In the distance, the Judean hills glimmer like bashful phantoms, wrapped in their pall of unbreachable mystery. While the Dead Sea hides behind a shimmering wall of grey gloom, as if ashamed of its relentlessly shrinking shores.

Unless something is done soon to curb this catastrophic phenomenon, the sea is destined to disappear into an insignificant borehole. There was a time when talk of a canal, the Dead-Med, linking the Dead Sea to the Mediterranean was being mooted as the most plausible means of salvage or salvation, but that dream seems to have evaporated.

I remember the time I was a young teacher and with a couple of colleagues decided to embark on a daring but hazardous cycling trip from Jerusalem down to the Dead Sea. It was downhill almost all the way, except when we neared the Khan El Ahmar caravanserai, the legendary site of the Good Samaritan parable.

When we finally slumped down at the shores of the glorious lake, the languid waves washed up lavishly around our ankles, with no intimation of the creeping liquid attrition future years would spawn.

-- Arthur Hagopian, former press officer of the Armenian Patriarchate of Jerusalem, currently living in Australia, has just returned from a short visit to Old City after a 15-year hiatus. This is the second in a series of articles he will be writing in the wake of his brief sojourn there.

|

Redistribution of Groong articles, such as this one, to any other

media, including but not limited to other mailing lists and Usenet

bulletin boards, is strictly prohibited without prior written

consent from Groong's Administrator. � Copyright 2009 Armenian News Network/Groong. All Rights Reserved. |

|---|